Colosseum

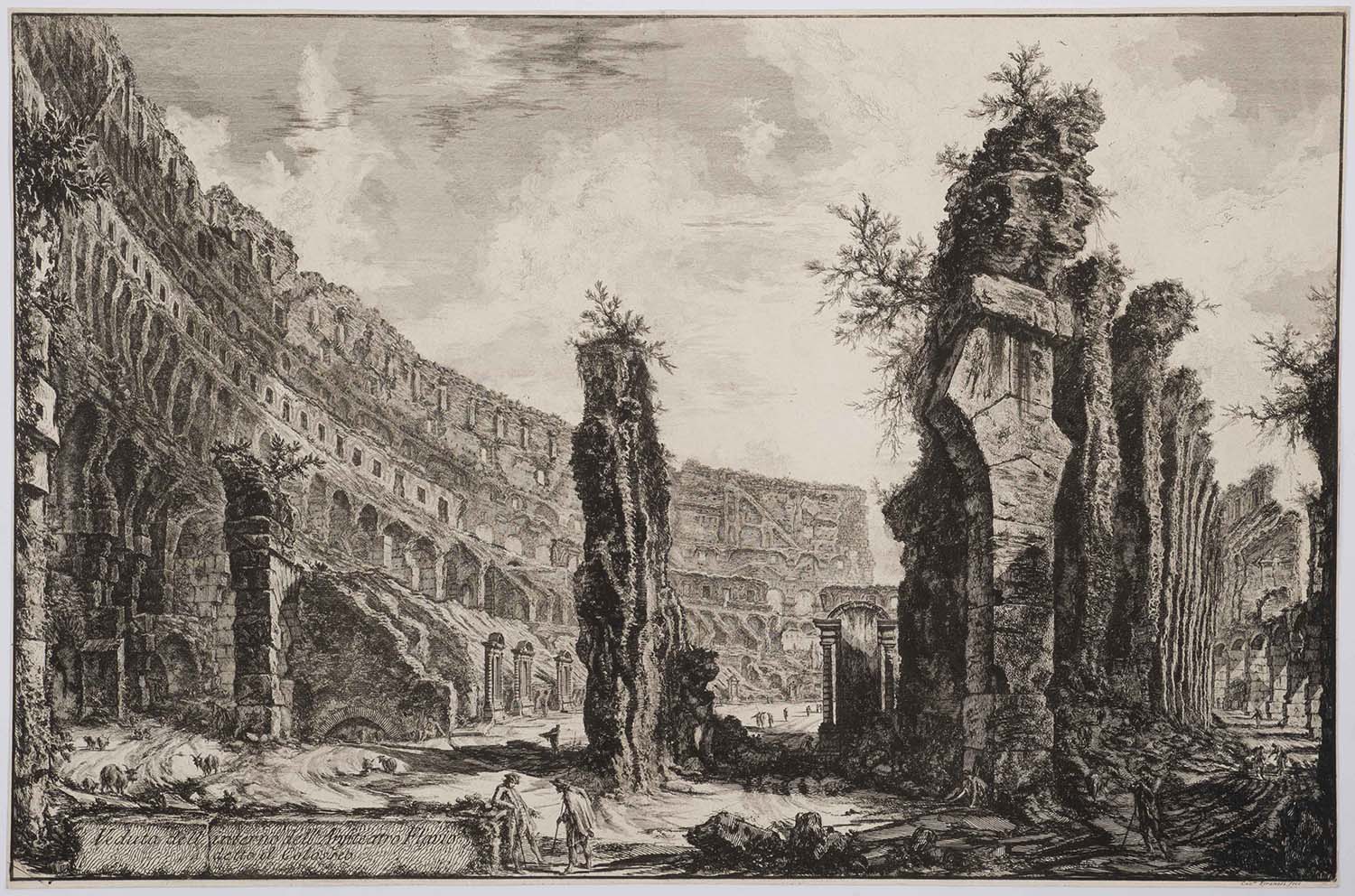

View of the interior of the Flavian Amphitheater called the Colosseum (Veduta dell'interno dell'Anfiteatro Flavio detto il Colosseo), from the series “Views of Rome,” c. 1766, etching on laid paper, Sheet/Page 17 15/16 H x 27 1/8 W in. Gift from the Trustees of the Corcoran Gallery of Art (Bequest of Frank B. Bristow), GW Collection (CGA.68.26.835)

By Rachel Pollack with contributions by Nour Burik and Megan Johnson

In the heart of Rome stands a testament to the ancient Romans’s reverence for blood-filled live entertainment: the Colosseum. Built during the Flavian Dynasty (ca. 69 - 96 CE), this iconic amphitheater was even hailed in its own day as a wonder of the ancient world. The Roman poet Martial proclaimed it greater than the pyramids of Egypt, the wall of Semiramis, the temple of Diana at Ephesus, and even the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus. At its peak, spectators of all social classes, from slaves to the emperor himself, eagerly watched innumerable violent battles between humans and animals alike. By the medieval and renaissance periods, this once-ancient wonder was used for a variety of purposes, including as a fortified residence by the Frangipani family in the twelfth century, a pilgrimage site consecrated in honor of Christian martyrs, and eventually a quarry for buildings across the Eternal City. Due to centuries of neglect and the absence of a centralized authority to oversee its preservation, much of the Colosseum fell prey to the forces of nature. Both vegetation and various animals, including livestock, were left to roam freely within its walls. By the time of Piranesi, the area around the Colosseum, including the Roman Forum and Palatine Hill, became a gathering place and home for the poor and marginalized.

These grand remains of ancient Rome sparked Piranesi’s enthusiasm; his appreciation for both structural engineering and the poetic ruins is reflected in every sure mark across his View of the Interior of the Flavian Amphitheater. Towering stone columns rise above majestic clouds, nestled among soft patches of moss and sparse tree branches, dwarfing the scattered figures below. These miniscule figures walk in the shadows of a greater, more prosperous past. Beggars in various forms of despair and shepherds leading trails of sheep through archways and winding dirt paths guide the viewer’s eye across Piranesi’s vast panorama. The artist invokes a charged atmosphere across the composition, made all the more complete by his intricate rendering of each rough-hewn archway and exposed brick façade. In a view perhaps even grander than the monument itself, Piranesi likewise created dramatic atmospheric contrasts and rich shadows across the entire composition. Light shines starkly down upon this ancient colossal ruin, reminding the viewer to take stock of what little remains of its interior. This is a common theme across many of the “Views of Rome,” in which the ruins reflect the tragedy of the human condition in the modern day and remind the viewer of the frailty of the ancient Roman Empire.

At the dawn of the eighteenth century, Rome became a center for arts and culture, attracting waves of tourists, artists, and architects from across Europe to endeavor upon the Grand Tour. The Colosseum was (and still remains) the central tourist attraction. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe was particularly moved by these iconic ruins at night, remarking, “Unless a person has walked through Rome in the light of the full moon he cannot imagine the beauty of it. All individual details are swallowed up in masses of light and shadow, and only the largest, most general images present themselves to the eye…The Coliseum offers a particularly beautiful sight.” In contrast, Piranesi’s view captures the Colosseum in the full light of day. Yet, the masses of light and shadow are no less evident in the artist’s view. Piranesi’s View of the interior of the Flavian Amphitheater reaches beyond the confines of representation, seeking instead to invoke a profound emotional connection between the viewer and this ancient monument. Even though the Colosseum is now nothing more than a ruin, it still fills viewers with a sense of reverence and silent awe.

View on Google Maps.

Bibliography

Martial, On The Spectacles, I