Grotto of Egeria

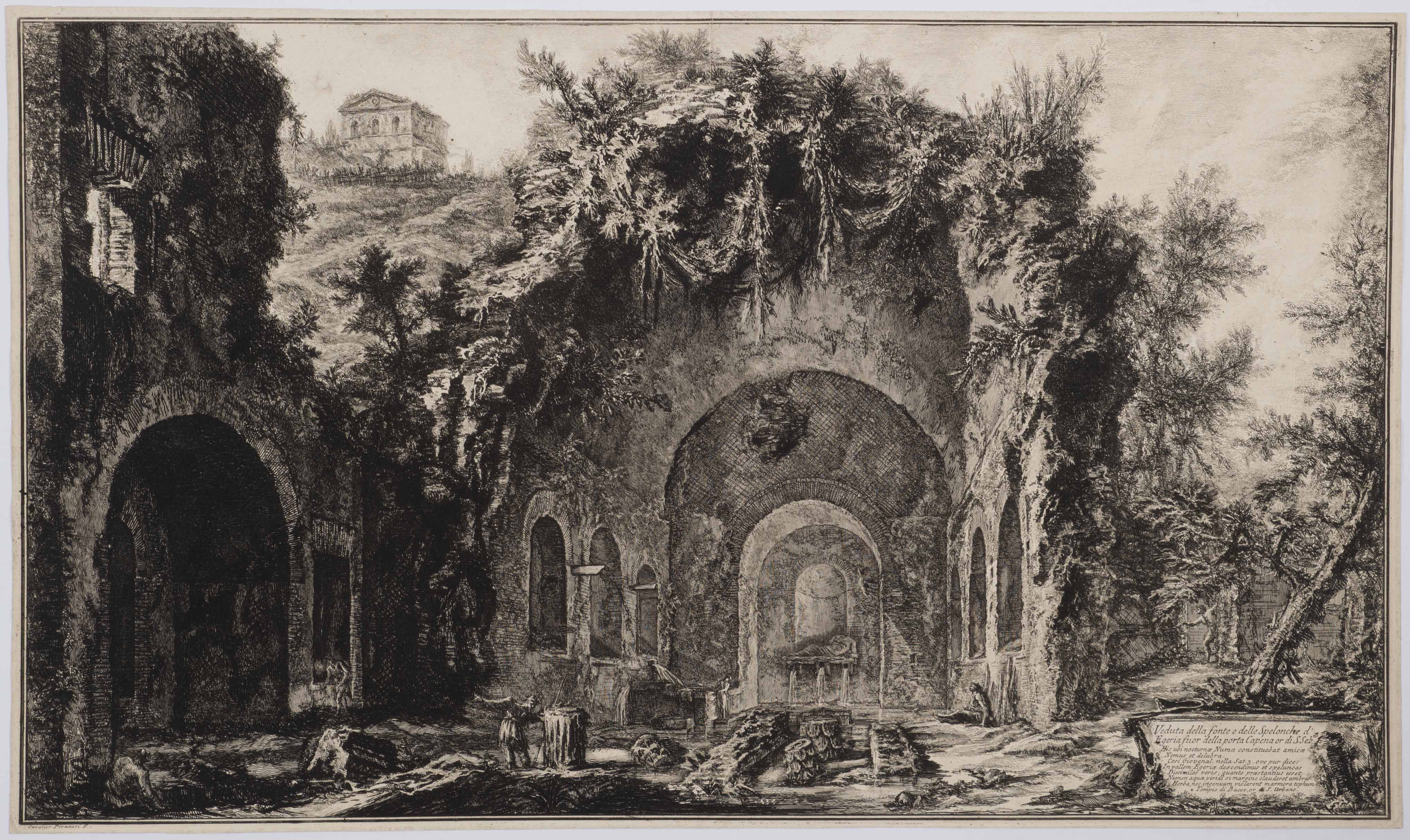

The so-called Grotto of Egeria (Veduta della fonte a delle Spelonche d'Egeria), from the series “Views of Rome,” c. 1776, etching on laid paper, Sheet/Page 16 1/8 H x 27 1/8 W in. Gift from the Trustees of the Corcoran Gallery of Art (Bequest of Frank B. Bristow), GW Collection (CGA.68.26.836)

By John Fine with contributions by Kidist Tulu

The Grotto of Egeria is traditionally associated with the legendary site where King Numa Pompilius held secret meetings with the mythical nymph Egeria. However, the identification of this monument is mistaken, as the actual site is situated at the base of the Caelian Hill, well within the Aurelian Walls. Despite this inaccuracy, the mythic associations of the grotto have captured the imagination of artists and authors for centuries, contributing to its enduring allure. Situated about a mile and a half outside the Porta San Sebastiano, the Grotto of Egeria overlooks the Valley of the Caffarella, one of the few areas on the periphery of Rome that still retains a pastoral character.

The rural setting and picturesque appearance have long attracted romanticists. In antiquity, the nymphaeum may have been part of the estate of Herodes Atticus, a prominent Greek rhetorician and Roman senator. This historical connection adds a layer of significance to the site, blending mythology with corroborated Roman history. The etching brings viewers into the central chamber of the grotto, offering a direct and intimate sensation.

In Roman mythology, King Numa Pompilius met with the nymph Egeria at her eponymously-named valley. Egeria advised the King on religious and legal reforms, shaping Rome’s early institutions and guiding Numa’s rule with divine counsel. Their relationship extended beyond an advisory role, and it was precisely their love which granted him this wisdom; as Plutarch’s Parallel Lives suggests, “the goddess Egeria loved him and bestowed herself upon him, and it was his communion with her that gave him a life of blessedness and a wisdom more than human.” According to Ovid’s Metamorphoses, Numa’s mortality brought Egeria immense sadness, as upon his death the goddess cried so many tears that she transformed into the fountain of water feeding this spring. Piranesi’s intimate portrayal invites viewers to engage more deeply with the grotto”s layered historical and cultural narratives, enhancing its mystique and reinforcing its significance as a place of contemplation and artistic inspiration.

The so-called Grotto of Egeria etching presents a detailed and expressive portrayal of this ancient sanctuary. Piranesi skillfully renders the interplay of light and shadow within the grotto, emphasizing its mystical and serene atmosphere. The grotto’s entrance is framed by lush vegetation, drawing the viewer’s eye into its depths, where faint figures add to the sense of mystical serenity. Piranesi skillfully depicts the abundance of flora hanging from the damp, moss-covered walls and vault. Classical architectural remnants, such as columns and carved stone, tie the site to its Roman heritage, combining visual beauty with rich historical and cultural significance, inviting viewers into this secluded and enchanted space.

This etching can be compared to Piranesi”s Interior View of the Cavern of the Acqua Virgo, a work in Piranesi’s “Campus Martius of Ancient Rome” series that captures the intersection of nature and classical antiquity. Both prints reflect an eighteenth-century fascination with ancient ruins and their romanticized portrayal. Romantics like Lord Byron commented extensively on the site, and as in his Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage, where Byron combines verdant imagery with romantic themes of immortal love and Egeria’s “all-heavenly bosom beating for the far footsteps of thy mortal lover.”

Piranesi's work also emphasizes the sublime beauty of these sites, portraying them as places of historical significance with awe-inspiring natural elements. A compelling contrast in depictions can be made with the works of the seventeenth-century Dutch Italianate artist Herman van Swanevelt, particularly given Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s references to the Baths of Caracalla. Specifically, Goethe points to the “solid masonry” which its builders used to stand up against “all causes of decay.” In contrast, Piranesi highlights the mysticism of the temple by choosing an angle from inside, revealing a once-hallowed ground where a mythical lover grieved for her lost partner. The so-called Grotto of Egeria’s grand and intricate detailing also evokes a sense of the sublime as defined by Edmund Burke in A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful. Burke describes the sublime as a quality that inspires awe through grandeur, astonishment, and some degree of horror, which is a concept well-suited to Piranesi’s approach. In this way, The so-called Grotto of Egeria transcends mere historical representation, instead presenting the site as a vital intersection of history, myth, and nature. Through Piranesi’s lens, this etching invites a sense of reverence, capturing the essence of the grotto as a sacred, contemplative space that bridges past and present.

More than just an illustrator, Piranesi had a unique vision that highlighted the sublime and eternal quality, yet fragility, of the structures, making them integral to Rome’s identity. His work captures the essence of Rome, ensuring that its historical significance remains alive in our minds while displaying its frailty. Through his evocative engravings, Piranesi's depictions continue to bridge the gap between the ancient past and the present, offering profound artistic insight that resonates to this day.

Inscription

Italian Portion:

Veduta della fonte e delle Spelonche d' Egeria fuor della porta Capena or di S.Seb

English Translation by Andrew Gibson:

View of the spring and of the Grotto of Egeria outside the Porta Capena or Porta San Sebastiano

Latin Portion:

Hic ubi nocturna Numa constituebat amicae Nemus et delubra. Cosi Giovenal nella Saturnus. 3. Ove pur dice: In vallem Egeriae descendimur et speluncas dissimiles veris; quanto prastantius esset Numen aqua viridi si margine clauderet umbrar Herba, nee ingenuum violarent marmora tophum. Tempio di Bacco, or di S. Urbano.

English Translation by John Fine:

Here, where Numa met his nocturnal girlfriend, So states Juvenal in satires. 3. Where he says: We descend into the valley of Egeria with its false grottos; how much more excellent the fountain’s power would be if its waters were enclosed by a side of green grass, and there were no marble to violate the native tufa. Temple of Bacchus, or of St. Urban.

Modern View

Photos courtesy of Dr. Pollack.

View on Google Maps.

Learn more about the Nymphaeum of Egeria.

Bibliography

Burke, Edmund, and Abraham Mills. A Philosophical Enquiry Into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful; With an Introductory Discourse Concerning Taste. New York, Harper, 1844. Pdf. Accessed online on November 5, 2024,. https://www.loc.gov/item/09013903/.

Byron, Lord George Gordon. “Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage.” Canto IV. New York, G. Munro, 1886. Accessed November 5, 2024. https://www.loc.gov/item/24023105/.

Goethe, Johann Wolfgang von. Letters from Switzerland and Travels in Italy, trans. A. J. W. Morrison London: G. Bell and Sons, 1892. Urbana, Illinois: Project Gutenberg. Retrieved November 5, 2024. https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/53205/pg53205-images.html#TRAVELS_IN_ITALY.

Haussler, Ralph. “Index.” Sacred Landscapes in Antiquity, July 31, 2020, 429–50. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv13pk5nv.38.

Menconero, Sofia. “Piranesi at the Nymphaeum of Egeria: Perspective Expedients.” Graphical Heritage, 2020, 343–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-47983-1_31.

Ovid. “Egeria Turned into a Fountain.” Book. In Metamorphoses, translated by Brookes More, Boston, MA: Cornhill Publishing Co., 1922. Perseus Digital Library. Ed. Gregory R. Crane. Tufts University. Accessed November 5, 2024.

Pinto, John A. “The Grotto of Egeria, before 1858.” City of the Soul: Rome and the Romantics, University Press of New England, 2016. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv1xx9k9w.65.

Plutarch. “The Life of Numa.” Book. In Lives Volume I, translated by Bernadotte Perrin. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1914.

Swanevelt, Herman van. The Grotto of the Egeria. 1641. Etching on laid paper, 8.5 x 27.8 cm (7 5/16 x 10 15/16 in.). National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. https://www.nga.gov/collection/art-object-page.53947.html.