Egyptian Obelisk

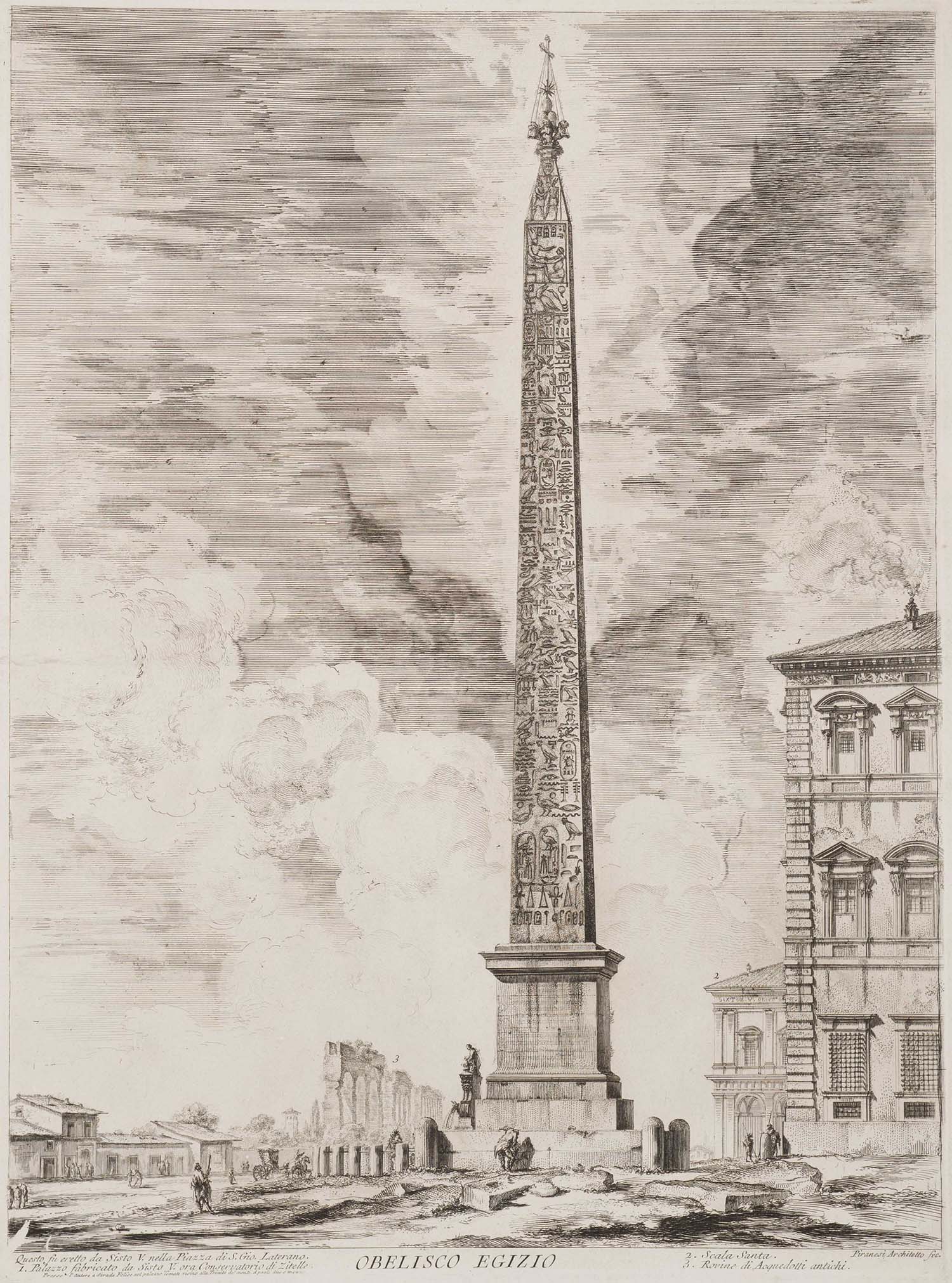

Egyptian Obelisk (Obelisco Egizio), from the series “Views of Rome,” Part I, c. 1759, etching on laid paper, Sheet/Page 24 1/16 H x 18 1/4 W in. Gift from the Trustees of the Corcoran Gallery of Art (Bequest of Frank B. Bristow), GW Collection (CGA.68.26.535)

By Alp Mustafa Mursit

The renowned printmaker Giovanni Battista Piranesi created the etching Egyptian Obelisk as part of his comprehensive documentation of ancient Roman monuments. This masterful work depicts the Lateran Obelisk, which stands at the Piazza di San Giovanni in Laterano, across from the Basilica of San Giovanni in Laterano. This etching exemplifies Piranesi’s distinctive ability for capturing architectural grandeur and monumental architecture, while also highlighting his exceptional mastery of intaglio printmaking.

The obelisk’s history spans over three millennia, representing one of antiquity’s most compelling narratives of cultural appropriation and transformation. Originally commissioned during the reign of Egyptian Pharaoh Thutmose III (1479-1425 BCE), it was erected at Karnak’s Temple of Amun under Thutmose IV. The obelisk’s journey to Rome exemplifies the complex logistics of imperial trophy-taking: Emperor Constantine I (306-337 CE) made an initial attempt to transport it to Constantinople, but abandoned this quest at Alexandria, Egypt. His son Constantius II (337-361 CE) finally succeeded in bringing it to Rome in 357 CE, positioning it within the Circus Maximus alongside the Flaminian Obelisk.

After centuries buried in fragments, having collapsed, the obelisk was excavated and restored under Pope Sixtus V’s (1585-1590) ambitious urban renewal program. Architect Domenico Fontana’s 1587 reconstruction reduced the monument by thirteen feet and approximately 100 tons. However, it still retained its imposing presence. The addition of a Christian cross at its apex and the ceremonial consecration symbolically transformed this Egyptian-Roman monument into a testament to papal authority and Catholic triumph.

Piranesi strategically positions the obelisk as the dominant vertical element, its commanding presence emphasized by the artist’s masterful handling of perspective and scale. In the background, the remains of a particular stretch of the Aqua Claudia aqueduct traces the horizon line, its arched form creating a dialogue with the obelisk’s stern verticality. These aqueducts stand as a testament to Roman engineering prowess and provide compositional balance to the scene. They evoke Rome’s technological achievements alongside its imperial might. At the same time, it should not be forgotten that these aqueducts now lay in ruins and remind the viewer of the eventual decay of the Roman Empire.

Piranesi’s rendering demonstrates his characteristic attention to archaeological detail while dramatizing the monument’s presence through masterful manipulation of perspective and atmospheric effects. The artist employs his signature annotative style, carefully numbering architectural features including the “Palace built by Sixtus V, now the Conservatory of Spinsters” and the Sancta Sanctorum with its holy stairs. These annotations reflect Piranesi’s commitment to both artistic interpretation and scholarly documentation.

Contemporary viewers can observe a striking contrast between Piranesi’s relatively sparse urban setting and today’s bustling cityscape. This transformation emphasizes how the obelisk has remained a constant witness to Rome’s evolution from late imperial capital to modern metropolis. The monument continues to exemplify Rome’s enduring capacity to absorb and transform cultural elements from across its empire, creating a uniquely synthetic architectural vocabulary that spans millennia.

Piranesi’s Egyptian Obelisk thus serves multiple functions: as a masterwork of eighteenth-century printmaking, a crucial archaeological record, and a meditation on the complex dynamics of cultural appropriation and transformation in European history. Through his precise technique and careful observation, Piranesi creates more than a mere architectural record; instead, he captures a monument in the ongoing dialogue between past and present, between Egyptian, Roman, and Christian traditions.

Inscription in Italian

Questo fu eretto da Sisto V. nella Piazza di S. Gio Laterano. 1. Palazzo fabricato da Sisto V. ora Conservatorio di Zitelle 2. Scala Santa 3. Rovine di Acquedotti antichi

English Translation by Andrew Gibson:

This was erected by Sixtus V in the piazza di San Giovanni in Laterano. 1. Palace built by Sixtus V, now the Conservatory of Spinsters 2. The Holy Stairs 3. Ruins of ancient aqueducts

Map View

View on Google Maps.

Bibliography

Piranesi, Giovanni Battista, “1720-1778: Obelisco Egizio.” National Library of New Zealand. https://natlib.govt.nz/records/23133696.

McGeough, Kevin M. “Imagining Ancient Egypt as the Idealized Self in Eighteenth-Century Europe.” Essay. In Eighteenth-Century Thing Theory in a Global Context, 89–113. Ashgate, 2013. https://scholar.ulethbridge.ca/sites/default/files/mcgekm/files/imaginingegypt.pdf?m=1458144700

Julius, Eline. “Obelisks in Late Antiquity: Roman or Egyptian? The Symbolic and Functional Meaning of Egyptian Obelisks in the Roman World in the 3rd and 4th Centuries AD,” From Leiden University's Student Repository. August 29, 2014. https://hdl.handle.net/1887/28377.

Voigts, Clemens, and E. C. Heine. "Constructing a discourse on the art of engineering: Domenico Fontana and the Vatican Obelisk." In Under Construction: Building the Material and the Imagined World (2015): 141-61.

Lowe, Adam. "An atemporal approach to Piranesi and his designs." In The Arts of Piranesi: Architect, etcher, antiquarian, vedutista, designer. (2012): 181-219. https://factumfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/An-atemporal-approach-to-Piranesi-and-his-designs.pdf

Quast, Matthias. "Fontana, Domenico." Grove Art Online, Oxford Art Online. 2003. https://shorturl.at/z8QEr

Parker, Grant. “Monolithic Appropriation? The Lateran Obelisk Compared.” Chapter. In Rome, Empire of Plunder: The Dynamics of Cultural Appropriation, edited by Matthew P. Loar, Carolyn MacDonald, and Dan-el Padilla Peralta, 137–59. Cambridge University Press, 2017.