Ponte Molle

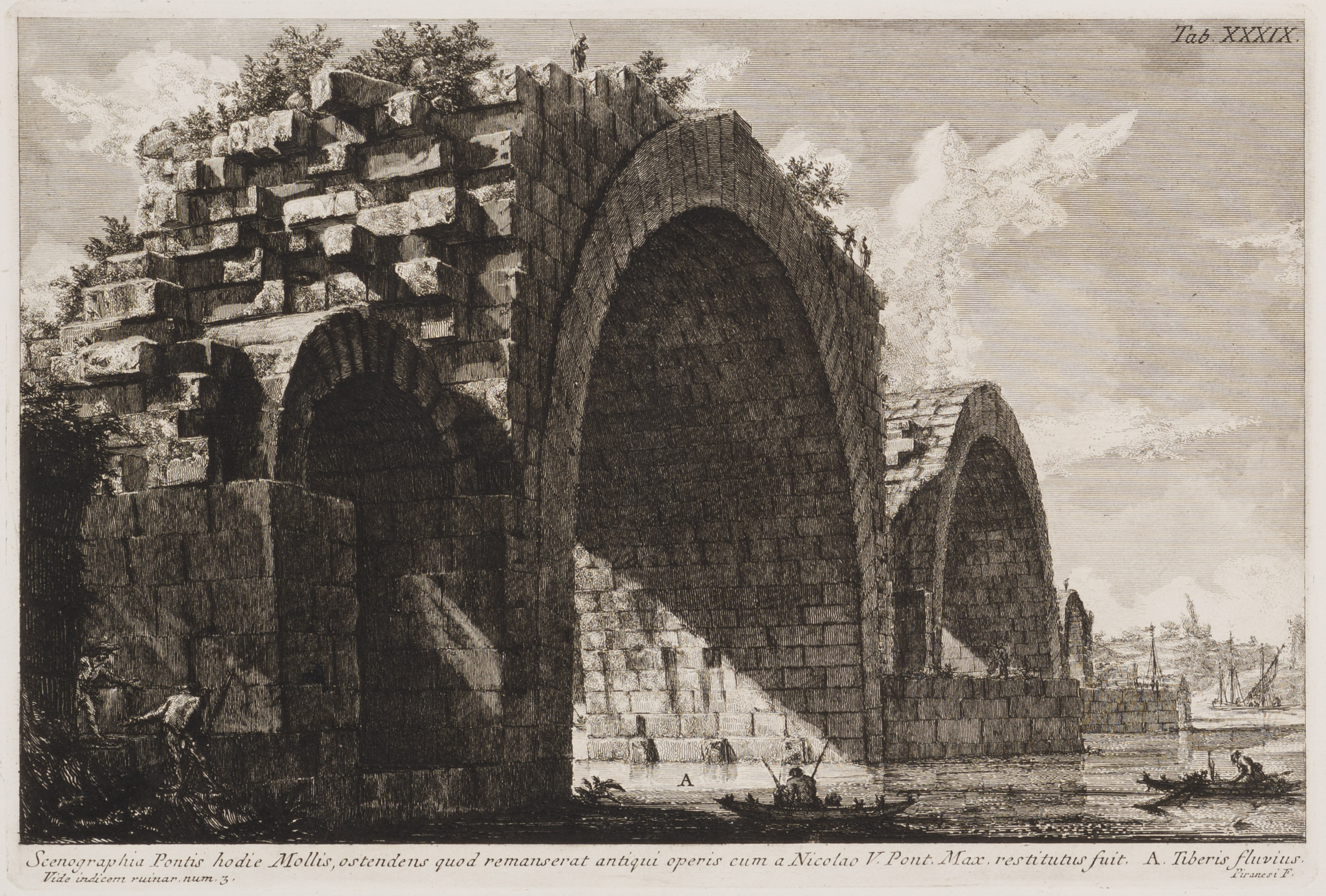

View of the Bridge Known as Ponte Molle (Scenographia Pontis hodie Mollis), from the series “The Campus Martius of Ancient Rome,” Plate 39, c. 1762, etching on laid paper, Sheet/Page 15 7/8 H x 21 1/8 W in. Gift from the Trustees of the Corcoran Gallery of Art (Bequest of Frank B. Bristow), GW Collection (CGA.68.26.527)

By Karoline Hirko

The Ponte Molle, better known today as the Milvian Bridge, spans over the Tiber River in Rome and is most famously known to history as the location of the Battle of the Milvian Bridge in 312 CE. At this very site, Emperor Constantine I defeated Maxentius. This victory ended the Tetrarchy and therefore secured Constantine I’s position as the sole emperor of Rome. According to early Christian sources like Eusebius of Caesarea, this battle gave rise to the empire’s conversion to Christianity. On the eve of this battle, Constantine I saw a vision of the Cross and marked his soldiers’ shields with the sign of the Cross.

Giovanni Battista Piranesi is meticulous and particular in his etching of this epic ruin. In View of the Bridge Known as Ponte Molle, the bridge’s weathered stones and impressive arches span across the Tiber River. Here, Piranesi focuses on its classical grandeur and its historical significance. Although the real-life bridge had been restored and was fully functioning in Piranesi’s lifetime, he deliberately chose to depict the structure in ruins – perhaps due to his fascination with the ruins themselves rather than their later modern restorations. He focuses solely on the magnificent shape of the bridge’s expansive arches and the broad landscape with the river flowing underneath it. Contemporary Romans precariously mill around near the keystone of the largest archway while various fishermen either gather near the steps of the riverbed or drift across the Tiber in dinghies. Piranesi was moved by the sublime beauty of these fragmented remains of antiquity, inspiring him to create an image of what the bridge would have become without preservation.

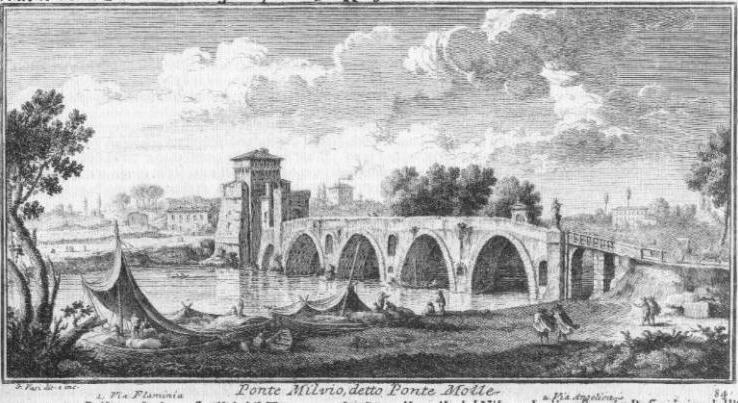

his is not the first time Piranesi depicted the Ponte Molle; he made other studies from different angles and focused on different aspects each time. The Ponte Molle (ca. 1762) from the series “Views of Rome,” or Vedute di Roma, was made around the same time as View of the Bridge Known as Ponte Molle. In The Ponte Molle, Piranesi depicts the bridge as it would have appeared in the eighteenth century with its modern restorations, making it a fully functional bridge in modern-day Rome. Throughout the Middle Ages and well into the modern era, the Ponte Molle underwent successive restoration campaigns and is now a historical site as well as a popular destination for tourists and locals.

The Ponte Molle has captured the imagination of numerous artists throughout history, such as Giulio Romano (ca. 1499-1546) in his fresco The Battle of the Milvian Bridge, the Dutch Italianate artist Jan Asselijn (ca. 1610-1652) in his painting The Tiber River with the Ponte Molle at Sunset, Piranesi’s teacher Giuseppe Vasi (1710-1782) in his engraving Ponte Milvio, and the Swiss artist Ernst Schiess (1872-1919) in his painting Ponte Molle. The Ponte Molle is famous for its battle and the battle’s impact on the empire’s conversion to Christianity. However, most artists from the seventeenth century onward preferred to focus on the picturesque character of this historic Roman ruin nestled amid the peaceful surroundings of the Tiber River’s banks. Piranesi’s etching View of the Bridge Known as Ponte Molle is both magically dreamlike and monumentally timeless.

Inscription in Latin

Scenographia Pontis hodie Mollis, ostendens quod remasnerat antiqui operis cum a Nicolao V. Pont. Max. restitutus fuit. A. Tiberis fluvius.

English Translation by John Fine:

A scene of the bridge today in Mollis, showing what remains of the ancient work, Pope Nicholas V restored it. A. The Tiber river.

Other Views of Ponte Molle

Giulio Romano, The Battle of the Milvian Bridge, c. 1520-1524, Fresco, Vatican Museums.

Jan Asselijn, The Tiber River with the Ponte Molle at Sunset, c. 1650, Oil on canvas, Overall 41.2 × 54 cm (16 1/4 × 21 1/4 in.),

Florian Carr Fund, New Century Fund, and Nell and Robert Weidenhammer Fund (2012.129.1)

Giuseppe Vasi, Ponte Milvio, c. 1741–43, Etching.

Ernst Schiess, Ponte Molle, c. 1913.

Giovanni Battista Piranesi, View of the Milvian Bridge over the Tiber two miles outside Rome (Veduta del Ponte Molle sul Tevere due miglia lontan da Roma), "Views of Rome," c. 1762, Etching, Sheet/Page 21 1/8 × 31 in. (53.7 × 78.7 cm), University Purchase, Director's Fund (1960.9.30)

Luigi Rossini, View of the Milvian Bridge over the Tiber (Veduta del Ponte Molle sul Tevere), "The Rome of Antiquity," c. 1822, Etching, Gift of Mrs. William L. Harkness (1927.124)

Jan Both, Ponte Molle, c. 1640s, Etching, Sheet/Page 7 1/2 × 10 11/16 in. (19.1 × 27.1 cm), Gift of Allen Evarts Foster, B.A. 1906 (1965.33.729)

View on Google Maps.

Bibliography

Blin, Arnaud. “Christianity Becomes a State Religion.” In War and Religion: Europe and the Mediterranean from the First through the Twenty-First Centuries, 1st ed., 41–78. University of California Press, 2019. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvcwn8sf.8.

Lang, Louis. “The Artists’ Pontemolle Association in Rome.” Bulletin of the American Art-Union, no. 7 (1851): 104–6. https://doi.org/10.2307/20646909.

Marshall, David R. “Piranesi, Juvarra, and the Triumphal Bridge Tradition.” The Art Bulletin 85, no. 2 (2003): 321–52. https://doi.org/10.2307/3177347.

Minor, Heather Hyde. “G. B. PIRANESI’S ‘DIVERSE MANIERE’ AND THE NATURAL HISTORY OF ANCIENT ART.” Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome 56/57 (2011): 323–51. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24616446.

Rosenfeld, Myra Nan. “Picturesque to Sublime: Piranesi’s Stylistic and Technical Development from 1740 to 1761.” Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome. Supplementary Volumes 4 (2006): 55–91. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4238468.

Stern, Michael. “For Piranesi, Imagination Trumps Classical Boundaries.” ProQuest, 2007. https://www.proquest.com/docview/2527533231?pq-origsite=primo%2F.

Serfass, Adam. 2022. MAXENTIUS AS XERXES IN EUSEBIUS OF CAESAREA'S ACCOUNTS OF THE BATTLE OF THE MILVIAN BRIDGE. Classical Quarterly 72, (2) (12): 822-833. https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/maxentius-as-xerxes-eusebius-caesareas-accounts/docview/2814682215/se-2.

“The Battle of Milvian Bridge and the History of the Book.” Library News, November 1, 2012. https://library.missouri.edu/news/special-collections/the-battle-of-milvian-bridge-and-the-history-of-the-book.

Wheelock, Arthur K. “The Tiber River with the Ponte Molle at Sunset, c. 1650.” NGA Online Editions, December 9, 2019. https://www.nga.gov/collection.html.