Saint Paul's

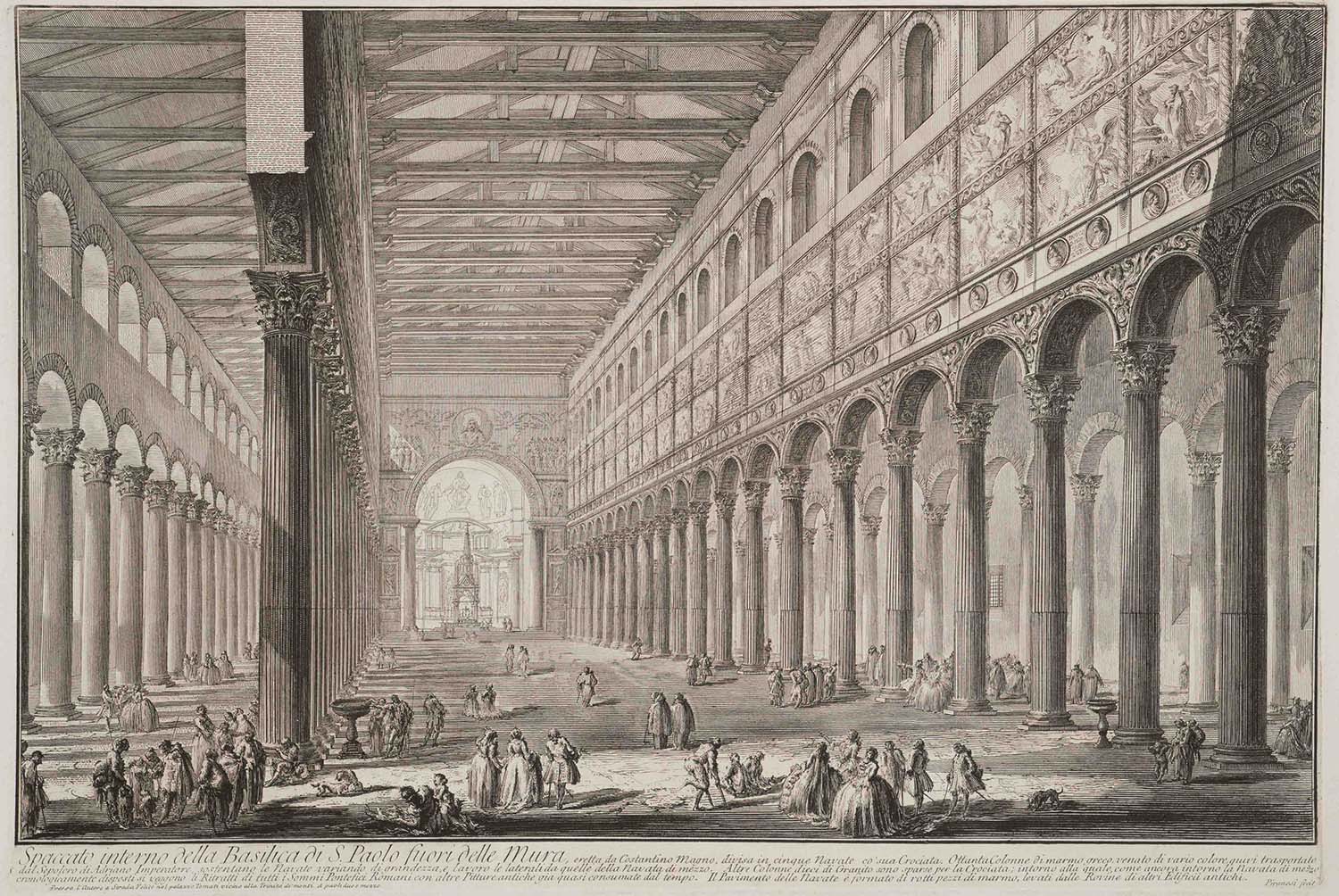

Cut-away view of the interior of the Basilica of S. Paul Outside of the Walls (Spaccato interno della Basilica di S. Paolo fuori delle Mura) from the series “Views of Rome,” c. 1749, etching on heavy ivory-laid paper, Sheet/Page 18 5/8 x 26 3/16 in. Gift from the Trustees of the Corcoran Gallery of Art, Bequest of Frank B. Bristow, GW Collection (CGA.68.26.832)

By Alexa Brown with contributions by Lila Thewes

The Basilica of Saint Paul Outside the Walls, one of the four papal basilicas of the Catholic faith, was commissioned in 386 CE by Roman Emperor Constantine the Great. It was the last imperially sponsored basilica constructed in Rome, two kilometers beyond the Aurelian Wall along the Via Ostiensis. Along with the later Saint Peter’s Basilica, Saint Paul Outside the Walls was a principal pilgrimage destination in Rome, attracting the attention of Piranesi and his primary clientele – aristocratic travelers who visited Rome. Piranesi depicts the larger basilica in his etching Cut-away view of the interior of the Basilica of S. Paul Outside of the Walls. Construction of this structure began under Valentinian II, Theodosius I, and Arcadius in 384 CE and was completed under Honorius around 403 CE, as indicated by a plaque placed by Pope Leo I in the mid-fifth century.

The centerpiece of Piranesi’s work is the basilica’s grand colonnade, composed of white marble shafts with distinct Corinthian capitals, contrasting against the red marble pillars adorning the chancel. The Corinthian capitals support the grand arches, creating an uplifting and spacious nave. However, this is one basilica area where Piranesi undoubtedly took artistic liberty. While certainly grand, the staffage used in his etching implies the columns are depicted on a larger scale than their actual size. Piranesi employs excellent contrast techniques to capture the tall arches, allowing natural light to flood the towering space. The altar at the end of the grand hall remains bathed in bright light, drawing the viewer’s attention as the composition's focal point. This interplay of dark and light elongates the room and imbues the space with a saintly clarity.

Beneath the altar lie the remains of Saint Paul the Apostle, often surmounted by a papal throne. From the pontificate of Gregory the Great (590-604 CE) and onwards, a papal throne stood at the center of the transept with the presbytery. This intentional juxtaposition served to justify pontifical spiritual authority through association with key relics in Rome’s basilicas. Similarly, Piranesi meticulously details a series of papal portraits spanning the length of the nave, each boasting its subject and a well-defined papal tiara. This tradition, dating back to the fifth century, emphasized the permanence of the Catholic Church and symbolized an uninterrupted succession from Saint Peter’s pontificate. Unfortunately, an estimated 158 papal portraits have since been lost to fire. Despite losing many original decorations, the basilica still has forty-two panels on the north wall depicting the life of Paul. Theodosius I originally commissioned these remaining panels in the fourth century. Numerous renovations took place throughout the centuries, including those undertaken by Pietro Cavallini from 1277 to 1279. Most of the frescoes are inspired by the life story of the Apostle found in the canonical Book of Acts. One of the frescoes in this series illustrates one of the earliest known representations of the meeting between the Holy Apostles Peter and Paul.

Piranesi’s magnificent composition encourages viewers to look upward, towards the light and the divine. However, the ground-level staffage, distinctly contemporary to Piranesi’s time, grounds the work in the mid-eighteenth century. Some aristocratic figures perusing the church's central nave might represent Piranesi’s clients or potential collectors of his “Views of Rome” series. Perhaps Piranesi knew that if his viewers had already had the opportunity to visit the real-life basilica, an ability to associate with a figure in his work might allow his art to function as a portal through which they could relive their blessed experiences. Piranesi’s etching also resembles a painting of the interior of the basilica by Giovanni Paolo Pannini, one of Piranesi’s contemporaries, further revealing the popularity of this particular subject during the eighteenth century.

The basilica's location along the Tiber’s riverbank left it susceptible to regular flooding, leading to unhygienic conditions and the outbreak of disease. This history of challenges peaked in the 1823 fire, which destroyed more than half of the complex, including the original wooden roof truss. Fortunately, Piranesi’s mid-eighteenth-century depiction captures the original structure before this devastating event. Despite commitments to a faithful reconstruction, many regard the present basilica as a “cold and lifeless counterfeit of the original.” Piranesi’s etching of Saint Paul’s Outside the Walls nonetheless testifies to the basilica’s hidden beauty with his use of meticulous details and perspective techniques to bring the building to life. In doing so, he transformed architecture into so much more than just a historical building, revealing its hidden intricacies and creating a piece that displays the building's everlasting beauty and his artistic mastery.

Inscription in Italian

Erette da Constantino Magno, divisa in cinque navate eo’sua Crociata. Ottanta colonne di marmo greco, venato di vario colore, quivi trasportate dal sepolcro di Adriano Imperatore, sostentano le navate varianto di grandezza, e lavoro la laterali da quelle della navata di mezzo. Altri colonne dicci di granito sono sparse per la Crociata: interno alla quale, come ancora interno la navata di mezza cronologicamente disposti si veagano li Ritratti di tutti i sommi Pontefici Romani con altre pitture antiche gia quasi consumate dal tempo. Il paviamento delle navate e formato di rotti pezzi di marmo, levati dalle rovine di altri edificii antichi.

English Translation by Andrew Gibson:

Cut-away view of the interior of the Basilica of St. Paul outside the walls, Erected by Constantine the Great, divided into five naves with its Crusade. Eighty columns of greek marble, veined in various colors, were transported here. You can see the portraits of all the Supreme Roman Pontiffs chronologically arranged alongside other ancient paintings almost worn out by time. The floor of the naves are made of broken pieces of marble removed from other ancient buildings.

View on Google Maps.

Bibliography

Camerlenghi, Nicola. “Splitting the Core: The Transverse Wall At The Basilica of San Paolo in Rome.” Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome 58 (2013): 115–42. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24616459.

Coarelli, Filippo, James J. Clauss, Daniel P. Harmon, J Anthony Clauss, and Pierre A. Mackay. “Western Environs: Viae Aurelia, Campana, Ostiensis.” In Rome and Environs: An Archaeological Guide, 1st ed., 437–43. University of California Press, 2014. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/j.ctt5vk043.20.

Grundhauser, Eric. “Basilica of Saint Paul Outside the Walls.” Atlas Obscura, September 23, 2014. https://www.atlasobscura.com/places/basilica-of-saint-paul-outside-the-…;

Kinney, Dale. "Review of St. Paul's Outside the Walls: A Roman Basilica, from Antiquity to the Modern Era, by Nicola Camerlenghi." Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 80, no. 4 (2021): 478-480.

Popkin, Maggie L. "Decorum and the Meanings of Materials in Triumphal Architecture of Republican Rome." Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 74, no. 3 (2015): 289–312. https://doi.org/10.1525/jsah.2015.74.3.289.

Rosenfeld, Myra Nan. “Picturesque to Sublime: Piranesi’s Stylistic and Technical Development from 1740 to 1761.” Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome. Supplementary Volumes 4 (2006): 55–91. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4238468.

Trout, Dennis. “(Re-)Founding Christian Rome: The Honorian Project of the Early Seventh Century.” Urban Developments in Late Antique and Medieval Rome, 149–76. Amsterdam University Press, 2021. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv1r4xczg.9.