Prisons

< Back

Imaginary Prisons

By Cristian Abarca

While publishing his Views of Rome, Piranesi began work on the Carceri d’Invenzione, or Imaginary Prisons, employing various etching, engraving, and burnishing techniques. The exact timeline of this project remains unclear, with estimates ranging from 1740 to 1747 for its inception and 1744 to 1750 for the first edition’s publication. While this initial fourteen-etching edition failed commercially, the sixteen-etching second edition of 1761 gained substantial renown.

The second edition’s success is attributable to its stark tonal contrast and heightened expression. Piranesi darkened the plates, added references to “impiety and the black arts,” and intensified the interplay of light and shadow to create a sculptural presence. His once lightly outlined structures became monumental, brutal objects, amplifying a darker, more Kafkaesque theme. Piranesi’s exploration of etching techniques to extend plate lifespan may have contributed to this darkening. He employed ink dabbing and improved line etching to minimize intersections, allowing plates to resist acid and retain more printing ink. These innovations enhanced the depth and durability of his etchings, contributing to the striking visual impact of the Carceri, particularly given their deep black color in the shadows.

The impetus for the Carceri series remains a subject of speculation. Political theorists suggest Piranesi used his work to critique the brutality of contemporary Italian governance. Vague medical records hint at a potentially life-threatening illness, leading some to speculate that Piranesi hallucinated these grand “prisons” in a fever-induced fugue state and then later devoted significant time to recreating them. Others propose, with varying degrees of seriousness, that drug use might account for the wonderous structures depicted in the series.

Three notable prints from Piranesi’s Carceri d’Invenzione include Title Plate (I), Prisoners on a Projecting Platform (X), and The Arch with a Shell Ornament (XI). These works exemplify the series’ key characteristics: imposing architecture, stark contrasts in scale, and a juxtaposition of the individual against institutional power. Such elements have led many to interpret the Imaginary Prisons project as a critique of the absolutist state.

Title Plate, from the series “Imaginary Prisons,” c. 1761, etching on wove paper, Sheet/Page 17 x 22 1/2 in. GW Collection, Transfer from Gelman Library, 2011. (P.11.10c)

Piranesi’s Title Plate immediately establishes the series’ themes of subterranean confusion and isolation. The series title, chiseled into immovable blocks of stone reminiscent of Roman travertine, suggests the permanence of Piranesi’s subject matter. The scene is dominated by massive ropes and chains weaving through vaulted ceilings, spikes, and grates, unequivocally declaring the space a prison. Despite grand staircases suggesting a path upwards toward the light, escape seems impossible. A central figure, bound atop the title altar, gazes solemnly into the dungeon below. His lifeless wings suggest a fallen angel caught between ascension and the menacing darkness below. In stark contrast, smaller figures on catwalks in the upper right observe the scene with detached curiosity and irreverence. This scale differentiation implies the bound figure represents a larger-than-human virtue, tragically restrained by earthly bonds. The observers’ inaction mirrors societal apathy, whether willful or born of confusion.

The complex network of stairwells and catwalks creates a disorientating environment, separating observers from the observed. This architectural labyrinth serves as a metaphor for societal hierarchy, trapping individuals in their predetermined positions. Throughout the series, this theme of inaction persists, reflecting either societal indifference or paralysis of those unable to navigate the convoluted structures of power. The ambiguity between purposeful paths and futile routes underscores the challenges of effecting change.

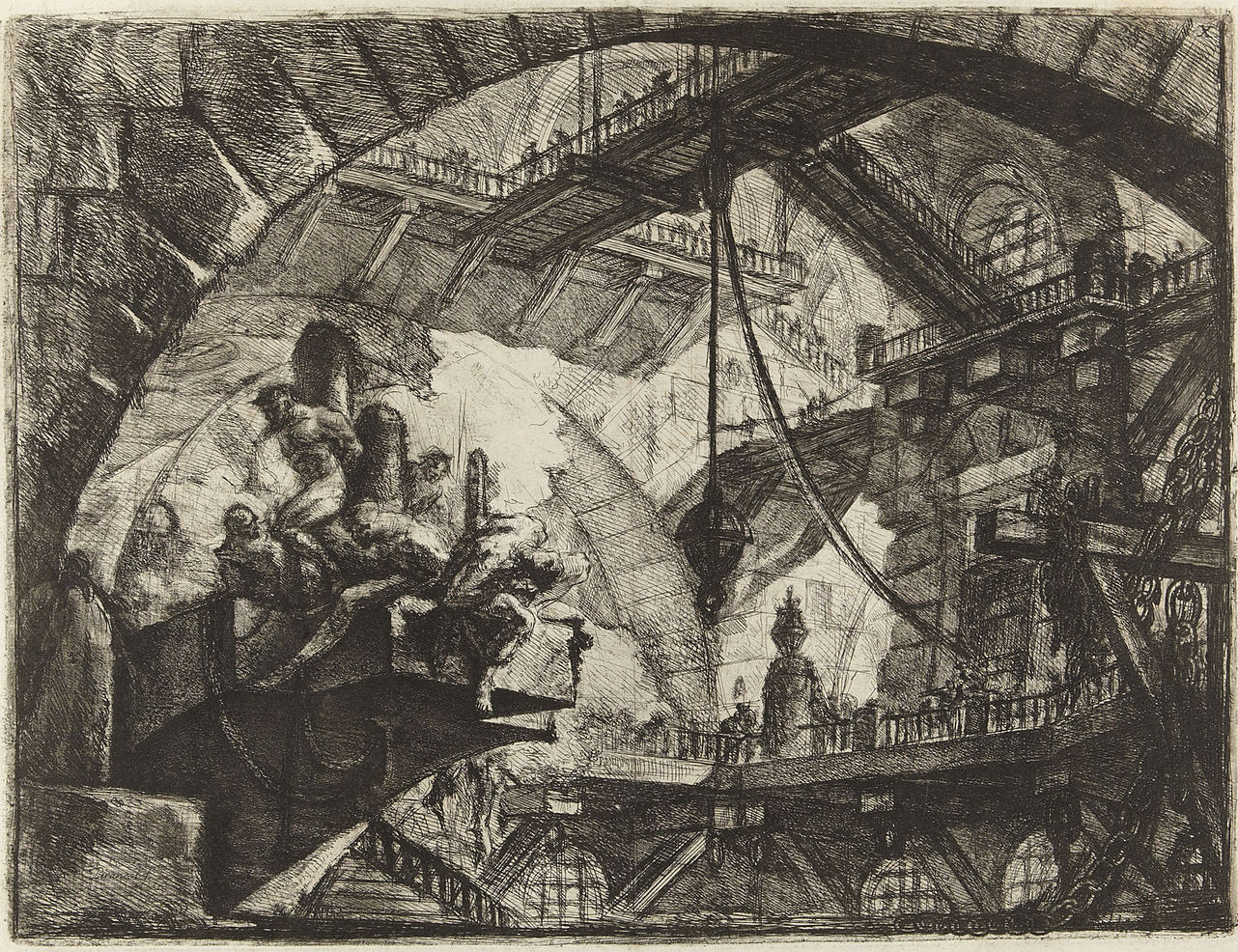

Prisoners on a Projecting Platform, from the series “Imaginary Prisons,” c. 1761, etching on wove paper, Sheet/Page 17 x 22 1/2 in. GW Collection, Transfer from Gelman Library, 2011. (P.11.10d)

In Prisoners on a Projecting Platform, Piranesi maintains his themes of isolation, confusion, and exploitation while introducing new elements. The titular platform features five prisoners chained to obscure pillars, their hands bound behind their backs. Unlike the angelic figure in the Title Plate etching, these prisoners appear to be ordinary men, more relatable to the viewer. However, their size relative to the onlookers remains disproportionate, presenting them as giants held accountable by seemingly insignificant people. This scale discrepancy extends to architectural elements, such as the ornate doorway looming above the small observers to the etching’s right.

The etching’s foreground depicts explicit torture, unique within the series. The horrific scene contrasts sharply with the ornate architecture of the cavernous hall, creating a jarring juxtaposition of beauty and brutality. Romanesque archways tower above the central plaza, while a complex network of bridges, stairs, and posts weaves across the image, particularly on the right. Chains and an ornate lantern suspend from these structures. Onlookers populate various levels, again as unwitting accomplices to the prison’s confinement. As with the Title Plate piece, the more one examines the structural layout in the Platform etching, the more confusing it becomes. The imposing architecture intimidates and isolates its victims, rendering the thought of escape hopeless, even if they could break free from their chains.

The Arch with a Shell Ornament, from the “Imaginary Prisons,” c. 1761, etching on wove paper, Sheet/Page 17 x 22 1/2 in. GW Collection, Transfer from Gelman Library, 2011. (P.11.10e)

Lastly, in The Arch with a Shell Ornament, Piranesi focuses on a grand arch spanning the scene's width, creating the most architecturally impressive plate of the series. The etching draws inspiration from Roman construction, featuring vaulted ceilings, bridges, beams, and numerous balconies that convey their permanence through their stone design. Despite this brutalist aesthetic, softer elements emerge, such as the grand staircase beneath the archway where figures meander.

Piranesi continues placing small characters throughout the scene, from high bridges to the lowest levels of the complex. Most notably, figures atop the central arch extend their arms, appearing to direct the operations of large machinery below. Unlike previous plates, the foreground is shrouded in shadow, obscuring the mechanisms and their potential victims. Shadowed figures cower at the base of a massive pillar to the left, silently suffering. This image presents a more sanitized version of a prison, its elegance and beauty diminishing the hideous elements and purposes it serves. The aspects society might prefer to overlook remain hidden in shadow despite their presence at the forefront of our world.

The foreground gains prominence in Piranesi’s series through strategic framing of the viewer’s perspective. Each work positions the spectator remarkably low, causing the structures to tower above, an effect likened to “seeing the bow of an ocean liner from a rowboat.” While Piranesi often used this technique to aggrandize Roman architecture in his Views of Rome series, its application here takes a darker turn, suggesting the viewer’s own imprisonment. While the figurative inspiration remains a subject of speculation, the physical modeling undoubtedly reflects the Roman ruins and monuments Piranesi studied for decades. The series’ subterranean structures mirror the chambers often found in Roman amphitheaters, offering a glimpse into the architectural marvels now lost to time.

In particular, The Arch with a Shell Ornament leaves the viewer with a profound sense of human insignificance. It expresses a unique brand of surreal disorientation that foreshadows the dystopian and absurdist elements in the works of authors like Orwell and Bradbury. Similarly, Piranesi’s architectural and engineering choices are reminiscent of optical illusions such as the Penrose stairs or M.C. Escher’s staircases, forging a sense of confusion and spatial ambiguity.

These imaginary prisons serve multiple purposes, punishing their victims both physically and psychologically, as explored in the work of French philosopher Michel Foucault. They isolate their subjects through confusion while maximizing observation and surveillance, echoing early principles of the panopticon. Scholars have used Foucault’s Discipline and Punish and Piranesi’s Carceri project as critical lenses to examine each other, reinforcing the interpretation of the artistic series as a critique of brutal methods employed in contemporary Italy and reminding viewers of state power.

The Kafkaesque nature of Piranesi’s prisons has inspired a rich history of fine art focused on incarceration. It inspired Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Pit and the Pendulum,” a short story that explores the sensations of torment, and Horace Walpole’s novel The Castle of Otranto, which is set in an imaginary Italian dungeon. Piranesi’s work even transitioned into the dimension of reality with British architect George Dance the Younger’s design of Newgate Prison in London, heavily inspired by the Carceri.

Ultimately, the series frames imprisonment as an indefinite struggle between the spirituality of the soul and the reality of the physical world. Piranesi's Imaginary Prisons project remains one of his most acclaimed endeavors, an iconic series that embodies the concept of imprisonment and the resulting physical or psychological anguish. Through their collectively robust and absolute narrative, these etchings connect with viewers in a way that is unparalleled in the medium, cementing their place in art history.

Bibliography

Altdorfer, John. "Inside A Fantastical Mind." Carnegie Magazine: Winter 2008, Winter 2008. https://carnegiemuseums.org/magazine-archive/2008/winter/article-123.html.

Carrabine, Eamonn. “Reading Pictures: Piranesi and Carceral Landscapes.” Journal of Narrative Criminology, 2019, 10–12. https://repository.essex.ac.uk/25419/.

Foucault, Michel. “‘Panopticism’ from ‘Discipline & Punish: The Birth of the Prison.’” Race/Ethnicity: Multidisciplinary Global Contexts 2, no. 1 (2008): 1–12. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25594995.

Hind, A. M. “Giovanni Battista Piranesi and His Carceri.” The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs 19, no. 98 (1911): 81–91. http://www.jstor.org/stable/858579.

Hirst, Paul. “Foucalt and Architecture.” AA Files, no. 26 (1993): 52–60. http://www.jstor.org/stable/29543867.

MacDonald, William Lloyd. Piranesi’s Carceri: Sources of Invention. Northampton, Massachusetts: Smith College, 1979.

Mayor, A. Hyatt. “Piranesi.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 33, no. 12 (1938): 279–84. https://doi.org/10.2307/3256393.

McClanahan, Bill. “Punishment, Prisons, and the Visual.” In Visual Criminology, 1st ed., 91–110. Bristol University Press, 2021. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv1sr6gxt.12.

McKiernan, Mike. “Giovanni Battista Piranesi Imaginary Prisons (Carceri d’Invenzione) Plate VII ‘The Well’ 1760.” Occupational Medicine 67, no. 1 (January 2017): 5–6. https://doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kqw174.

Pach, Walter. “Imagining Democracy, Punishment, and Infinity: Giovanni Battista Piranesi’s Carceri d’invenzione.” Comparative Literature Undergraduate Journal 12, no. 2 (April 1, 2022). https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1pc602bp.

Piranesi, Giovanni Battista. The Prisons (Le Carceri): The Complete First and Second States. New York, New York: Dover Publications, 1973.

Rosenfeld, Myra Nan. “Picturesque to Sublime: Piranesi’s Stylistic and Technical Development from 1740 to 1761.” Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome. Supplementary Volumes 4 (2006): 55–91. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4238468.

Yourcenar, Marguerite. "The Dark Brain of Piranesi and Other Essays." Henley on Thames: Ellis, 1984.